By Md. Shahidul Islam from Rajshahi

Introduction

The Barind region, located in the drought-prone northwestern part of Bangladesh, is an ecologically diverse yet environmentally vulnerable zone. Challenges such as water scarcity and the impacts of climate change have made agriculture and daily life in this area increasingly difficult. Over the past decade, the widespread adoption of plastic-dependent agricultural practices has significantly degraded soil fertility, disrupted water systems, and harmed the natural balance of the environment. However, there is hope. Local farming communities are initiating a new journey toward plastic-free agriculture and sustainable living. This is not merely a shift in technology but a deeper cultural and ethnographic transformation.

Plastic and Agriculture: A Crisis in the Barind Region

According to local farmers and elders from Naogaon, Rajshahi, and Chapainawabganj districts, the use of plastic in agriculture increased significantly after 2010. Common examples include plastic mulch sheets for crops, plastic bags for fruits, plastic irrigation pipes, and packaging for seeds and pesticides. Field data reveal that most farmers are unaware on how to properly manage this plastic waste. These materials do not decompose and cause long-term soil pollution. More than just an environmental threat, plastic has disrupted indigenous agricultural knowledge, local culture, and traditional health practices. Previously, agriculture relied on cow dung, compost leaves, and home-conserved seeds. Today, these practices are disappearing fast.

Agroecological Practices and the Transition Toward Plastic-Free Farming

BARCIK has playing a supportive role in promoting agroecological practices, local knowledge systems, climate justice, and food and seed sovereignty since 2010 in the region. BARCIK has established an ongoing process in the Barind region that prioritizes nature-based solutions through encouraging environment friendly and nature resource-based farming placing the community in the centre and recogning their knowledge. Between 2023 and 2025, a significant transformation has been observed in eight villages across five unions in the Tanore, Poba, and Nachole subdistricts of Rajshahi and Chapainawabganj. These villages include Gokul-Mathura, Mohor, Mondumala Mahali Para, Dubaiil, Sindukai, Haridevpur, Bilnepal Para, and Kharibona. Here, both men and women farmers are exchanging knowledge and experiences to establish agroecological practices and processes through maintaining plastic-free lifestyles. The following characteristics have emerged from direct field observations and participatory engagement:

Revival of Local Resources and Indigenous Techniques

Farmers have returned to using composted liquid fertilizers and natural pesticides made from red chili and neem leaves. Instead of plastic, they use clay pots, earthen jars, and bamboo containers for storage and application. One prominent example is Ms. Sultana Khatun, a farmer from Darshanpara Union in Poba, Rajshahi. She has been practicing agroecology and helping others to adopt these methods for the five years. She has set up an agroecological learning center (ALC) at her home, producing natural biopesticides in clay containers and encouraging others to do the same. She has contributed to the development of 20 model shotobari households, each capable of meeting their own food and seed needs through nature-based farming. So far, BARCIK has supported the development of 201 such shotobari model and 8 agroecology learning centers (ALCs) in the region. None of these centers use plastic materials. Through their efforts, they aim to send a strong message to society: “We can live without plastic, and plastic is endangering our lives, nature and agriculture.”

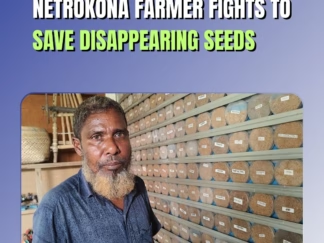

Seed Sovereignty and the Fight Against Plastic

Women are creating seed bags from old fabric, jute, or banana leaves. For long-term storage, they use glass jars, clay pots, and earthen containers instead of plastic. They also preserve grains using indigenous techniques such as sun-drying, maintaining optimal temperature, and applying cow dung coating without any chemical pesticides. These initiatives are led by “Community Seed Banks,” managed primarily by women. These banks are grassroots responses to the plastic crisis and support the conservation, exchange, and promotion of locally adapted, drought-resistant, and traditional seed varieties. Notably, no plastic is allowed in the seed banks.

According to data and information from BARCIK’s fieldwork and community records, by May 2025, 15 community seed banks have been established in Tanore and Poba (Rajshahi), and Nachole (Chapainawabganj). In the last three years, each bank has provided seeds to an average of 4,500 farmers. The use of native seeds has increased, and previously lost varieties have been revived.

For instance, Ms. Sultana Khatun of the Bilnepal Para Seed Bank said, “Three varieties of potatoes had disappeared from our area. We collected them from Nachole and have now reintroduced all three.” Farmer Raihan Kabir Ranju from Nachole said, “Thanks to the seed banks, drought-tolerant varieties are increasing, and we conserve all seeds in our own made bags totally abandoning the use of plastic.” Another woman, Ms. Kabuljan of Haridevpur, said, “We keep seeds in our traditional way, not in plastic. Plastic harms us. We won’t harm ourselves or let others do so either.”

Revaluation of Local Knowledge and Intergenerational Participation

Many traditional practices that protect nature which tested over thousands of years are being revived and shared. For instance, during severe cold, farmers sprinkle water on seedbeds to protect them. Local pest control and plant-based remedies are becoming common again. At BARCIK’s Haridevpur Agroecology Learning Center, a garden of uncultivated and medicinal plants has been created. School students visit to identify and learn about their uses. This has increased awareness and interest among youth in protecting biodiversity and seeds. On othe other hand, a nearby school named Taland Anandomohan High School has even established a seed library in 2019. Students and teachers exchange indigenous seeds, grow vegetables at home without chemicals, and have banned plastic from the library’s operations.

Ethnographical Analysis

This transformation is not just technological but deeply social and cultural. It can be viewed through three anthropological lenses:

- Ecological Anthropology: This movement reflects a conscious effort to reconnect humans and nature. Farmers have realized that plastic pollution affects both the environment and human health. They now understand that survival depends on maintaining a healthy ecosystem. Humans cannot thrive by harming nature, they must coexist in interdependence.

- Gendered Knowledge and women Leadership: Women have emerged not only as cultivators but also as seed guardians, nutrition caretakers, and environmental stewards. They are leading this transformation, supported by BARCIK’s efforts to increase their knowledge and experiences.

- Anthropology of Movements: This is a silent revolution, a “soft resistance” where communities are redefining their lives without external imposition. It is not confrontational but a strategic, ground-level protest that influences both soil and society.

Health and Social Well-being

Ethnographic observation shows that these agricultural changes have improved health and wellbeing. Skin diseases in children have decreased, water pollution has reduced, and respiratory issues among women have decreased. Farmers are producing at lower costs, which enhances their self-respect and food security.

Challenges and Policy Relevance

Despite its promise, this movement faces challenges. Plastic-dependent supply chains still dominate the agricultural market. There is limited enforcement of environmental laws and insufficient policy support for plastic-free farming. Training and research in natural agriculture are lacking. Therefore, government and NGO projects must discourage plastic use and integrate anti-plastic initiatives. National policies and support mechanisms are essential to empower local knowledge and initiatives like these.

Conclusion

The plastic-free agriculture and lifestyle movement in the Barind region is not just an environmental innovation, it is an ethnographic awakening. It redefines how people relate to land, life, and society. This movement teaches us that true development does not lie in external solutions, but in reactivating internal knowledge, culture, and practices. What has begun in the hands of Bangladeshi farmers is not just an ecological effort, it is a struggle for freedom, dignity, and sustainability. We perceive, only through the collective efforts of the state, society, and citizens will transform it to a national movement connecting and involving more people under the umbrella of this movement to ensure a plastic free life, nature and agriculture.

Sources

- Direct field observations in BARCIK working areas

- Participation and observation in BARCIK and community programs

- Interviews and thematic discussions

- Focus group discussions and meetings

- BARCIK’s monthly and annual progress reports

Md. Shahidul Islam

Anthropologist & BARCIK’s Regional Coordinator